It is said that good things come to those who wait, an optimistic phrase demanding patience, often in the face of hard times, and doubt.

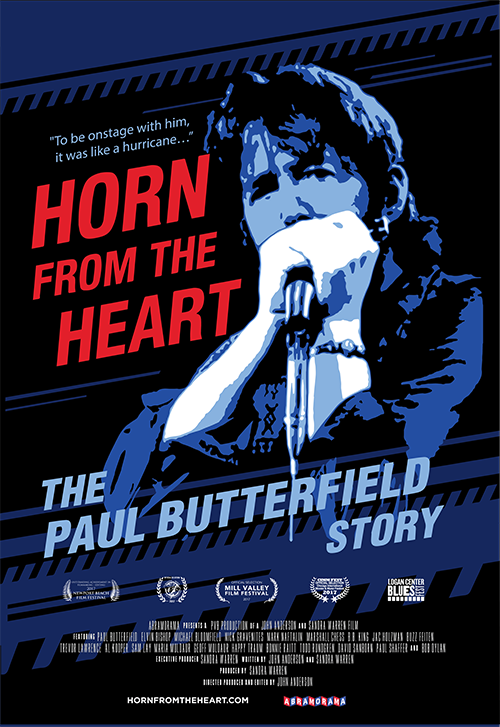

Though many would argue that Paul Butterfield was a game changer, innovator and rule-breaker, taking the harmonica and the blues to a whole new level, there was very little beyond his recordings to document his life. Harmonica players and blues lovers, anxious to learn more about him and his music, would find no books or films dedicated solely to the bluesman, and not much in the way of archival footage.

But, as we said, good things come to those who wait. And, thanks to Sandra Warren, John Anderson and Abramorama, the wait is over.

The Life of a Legend

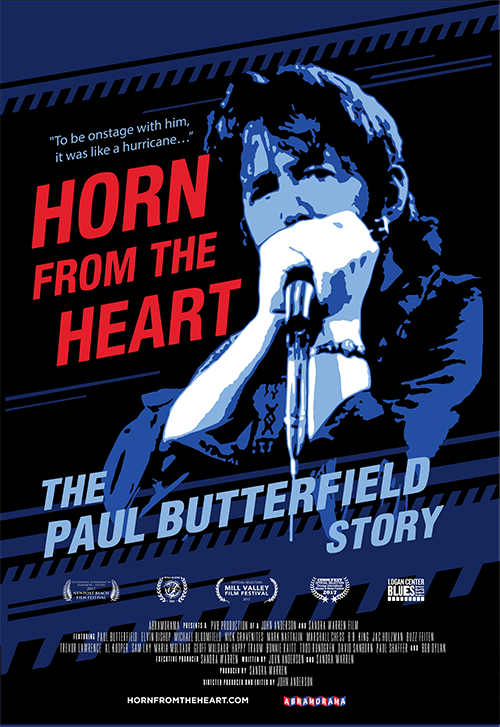

Now a documentary film, Horn from the Heart, offers up a wide and glorious assemblage of musicians, friends, neighbors and family members, anxious to share their memories and secure Butterfield’s place in the world of music. (See the trailer at the top of this page)

He was born just before Christmas, on December 17, 1942. His mom was an artist, his dad, an attorney. They lived a comfortable life in the Hyde Park section of Chicago’s South Side, where his parents introduced him and his brother Peter to music at a young age.

Paul took up the flute when he was in high school, taking lessons from a well-respected flautist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. And though the instrument was never a part of the music he would later play on stage or record, there are those who recall him taking his flute with him on the road and playing it backstage or in his hotel room every now and again.

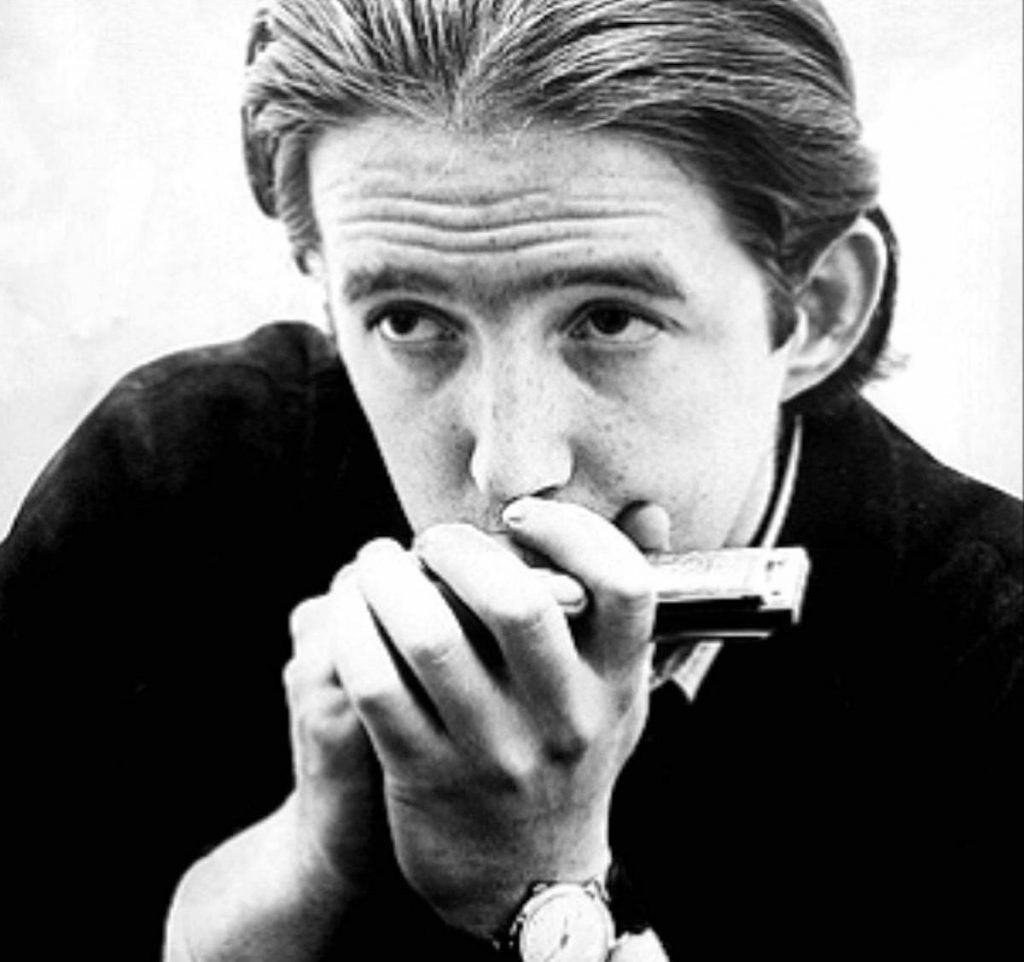

His relationship with the harmonica was different, special. Those who were around at the very beginning of that relationship recall how totally absorbed he was in learning the ins and outs of the instrument that sang to him.

That would never change.

An Imperfect, Complicated Soul

Peter remembers Paul going off on his own, working his way around the harp in quiet seclusion. “You’d know not to bother him,” he says, adding, “He was totally absorbed.”

Paul Butterfield was, by most accounts, an imperfect and complicated soul, as many great artists are, and the film’s contributors speak openly about what he was and wasn’t, in equal measure.

More than one person in the film notes that he wasn’t “warm and fuzzy”— their term, not ours.

We also learn that he wasn’t into chit-chat, tending friendships, accepting things that were unacceptable or drawing lines in the sand, whether you were talking music or race relations.

And he wasn’t out for the glory, which is to say that when it came to blowing his own horn, he wasn’t into self-promotion.

What he was, was in it for the music. Pure and simple. All the way. All the time.

As Trevor Lawrence put it, “He was a real blues guy.”

Original band member Elvin Bishop recalls that, when he first met him, “Butter”— as his friends called him — primarily played the guitar, but that within six months of picking up the harmonica, he was “a natural genius on the instrument,” getting “way good in a short amount of time.”

And yet, a track and field scholarship to Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island seemed to be pulling Butterfield in a different direction —away from music, and what was considered to be the urban blues capital of the world.

When Fate Steps in

But fate literally stepped in, when the college-bound high school grad tripped over a rake. The resulting knee injury put an end to the scholarship, keeping Butterfield in Chicago, where he enrolled in the University of Illinois.

It was there that he met Nick Gravenites, a young songwriter/guitar player who shared his love of the blues. The two began hanging out at the city’s numerous blues clubs where they were often the only white faces in the room.

While many throughout the film note that, while he was a great admirer of those who came before him, Butterfield’s aim was never to copy their styles, licks, or techniques, but rather to learn from them.

Says Bishop: “The good thing about Butter was, he was one of the few harmonica players you’ll ever see who wasn’t dominated by Little Walter he was always himself.”

Jim Kweskin, whose jug-band music would later captivate the Boston college crowd, met the then 19-year-old while on a visit to Chicago, where Butterfield introduced him to the music of some of the town’s greatest blues players, among them Muddy Waters.

“I got the feeling that Muddy liked Paul a lot,” he says, “and that he was glad to teach him and show him and have somebody — a young person, specifically a young white person — who could already play great blues harmonica.”

At some point, Paul gathered enough self-confidence to ask if he might sit in with the guys from time to time, which, notes Peter, was particularly courageous, not only because it took no small amount of gumption to think that he could keep up with them, but because he was of a different race and, when you consider that this was before the civil rights movement took hold, such a request could have been viewed with no small amount of wariness.

But, as those who were there note, he was both welcomed and encouraged, not only by Waters, but the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter. The fact that color didn’t enter into the equation on either side of the bandstand was, in itself, quite remarkable.

As time went on, the ties that bound Butterfield to his studies could no longer stand up to his need to make music, resulting in his spending less and less time hitting the books and more and more time hitting the clubs. He eventually dropped out of college, much to his parents’ chagrin. Seeing no future in their son’s current modus operandi, and losing patience, they urged him to “get serious”, get a job and get on with his life.

Butterfield Hits the Streets

But the thing was, the harmonica was his life, and so it was that he and Nick took their music to the streets, or at least the city’s coffee houses and campus parties. They called themselves — what else but Nick and Paul, with Nick on guitar, and Paul doing double duty, singing and wowing crowds with his electrifying way around the diatonic. This, while continuing to sit in with the masters at every opportunity.

And opportunity came knocking in the summer of 1963 when Paul was approached by the owner of Big John’s, a blues club in the Old Town district of the city. He offered Butterfield a steady four-nights-a-week gig. All Paul had to do was put a band together and do his thing.

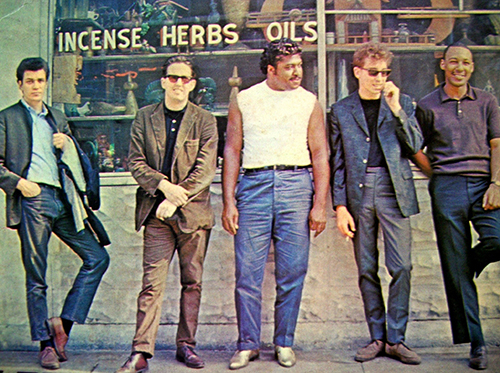

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band made its debut in the summer of ’63. “Meaner than a junk-yard dog,” it was a powerhouse of talent, with Butterfield on harmonica and vocals, Elvin Bishop on guitar and Sam Lay on drums, and Jerome Arnold on bass — Butterfield having wooed Lay and Arnold away from Howlin’ Wolf’s band by upping their pay from seven dollars a night to a whopping twenty bucks.

His gift for bringing the best musicians together, whatever their color, was mirrored by the make-up of the audience. Black and white, young and old, moved to the music, caught up in the electrifying sounds of this incredible checkerboard of a band.

Those who worked with Paul Butterfield during the club years recall that while he was not one to cultivate friendships, he let his band members know that he had their backs.

A Man of Morals

Says guitarist Buzz Feiten, “We were an interracial band where everybody was equal, but there were parts of the country that didn’t see it that way. People would say something to us and there were some near-confrontations with Butterfield because he would get in their face. He stood up for what he believed in.”

A poignant moment in the film comes when Mark Naftalin recalls a conversation between Butterfield and drummer Billy Davenport who was concerned about what he, as an African American appearing in an integrated band, might face on the road. As Naftalin tells it, Paul said to him, “Where you can’t go, we won’t go.”

“It meant something to him,” says Naftalin. “He got that guarantee, and it says something about Paul.”

Davenport loved him for it, as did all of the members of this big, ballsy band. They marveled at his outrageous talent and wanted to live up to his faith in them; but few got close to him. “He wasn’t much interested in other people,” says one former band member. Others describe him as very quiet, hard-edged, defensive, remote, and even on occasion, downright unfriendly — not exactly a poster boy for Mr. Personality!

His music was as ferocious as he was: big and loud, in what might today be described as blues on steroids. And it didn’t take long before word spread to Elektra Records producer Paul Rothchild, prompting him to head for Chicago and see what all the fuss was all about.

As Jac Holzman, founder and former Elektra CEO, tells the story, Rothchild heard two bands that night, the Butterfield Blues Band and Mike Bloomfield’s band. Bloomfield was a killer guitarist and, impressed, Rothchild urged Paul to take him on, but Butterfield said he had tried and failed. Not to worry; Rothchild’s influence eased the way, setting the wheels in motion that would make the hot band even hotter.

Throughout Horn From the Heart, we hear former band members talking about how much they loved playing with Paul. Bloomfield turned down a gig touring with the far more visible Bob Dylan to stay with him, telling guitarist Al Kooper, “I just want to play the blues, and I’m havin’ a great time doin’ it in this band.”

Life was good and getting better, but it was a complicated time in our country’s history. The Vietnam War was raging, flower power was making the news, and bubble gum rock and folk music’s simplistic chord progressions were being overshadowed by the harder, more complicated messages and structures that were coming out of England. Butterfield’s music, though a world away from the pop sounds of the day, was anything but benign, and his amplified, hard-hitting, in-your-face approach was in sync with the times.

Holzman took note, offering Paul a contract, something Peter says his brother had never envisioned happening.

The band was on a roll.

And Then… and Then…

He received his draft notice, and as every young man of a certain age knew, when they called your number, life, as you knew it, stopped. There were a few exclusions, but none of them applied to Paul. He was understandably devastated. Everything he had been working towards was now in jeopardy. Peter recalls his brother saying, “I almost had it, and it’s being taken away from me.”

And then… and then…

A young woman named Virginia McEwan stepped up to the plate, not only saving Paul’s career, reflects his brother, but also his life.

It was as if to say, “Yes, Paul, there is a Santa Claus.”

Virginia was a friend, nothing more, a barmaid at Big John’s who lived near Butterfield, often sharing a ride to or from the club. She was also very much against the war — an activist of sorts — and when she heard of Paul’s plight she offered to marry him, an act that would keep him out of the draft.

They married on November 16th of 1965, and would have a son, Gabriel, the following year.

No longer in jeopardy, the Elektra contract went through as planned and the band went into the studio to record their first album in 1964. Says Holzman, “I thought it was pretty good, and we pressed up ten thousand copies because the Paul Butterfield Blues Band had a track on Sampler #6 and it was selling well in Chicago. And it turned out that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was making it happen.” But Rothchild, who had produced the record, didn’t think it was as good as it could be, and wanted to scrap it and go back into the studio.

The resulting self-titled album featured Paul on Harmonica and vocals, Elvin Bishop on rhythm guitar, Michael Bloomfield on slide, Jerome Arnold on bass, Sam Lay on drums, and Mark Naftalin on organ. A note on the album’s back cover read: “We suggest that you play this record at the highest possible volume in order to fully appreciate the sound of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.”

Born in Chicago, with Paul Butterfield, Rick Danko and Blondie Chaplin

The first cut on the album, Born in Chicago, would wind up on a sampler album that introduced a broader audience to the band’s music. Among those who would be charmed by the band’s unique sound was a teenage Sandra Warren, who, some 50-plus years later, would co-produce HornFrom the Heart. Says Warren, “That cut changed my life and musical direction.”

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band album would eventually take the number eleven spot on Downbeat magazine’s All-Time Top 50 Blues albums.

Give Me a Hi-Fi!

It was Paul Rothchild who introduced Paul Butterfield to Albert Grossman. Grossman managed Bob Dylan and Peter Paul and Mary, and took the young band leader under his wing. It was the start of a close and complicated relationship between the two men, with Grossman becoming as much a father figure as a manager over the years. With his connections, the band would move to bigger and better venues that paid far more than the usual club date.

The band was on its way, as all over America, people were discovering a new kind of blues unlike anything they had heard before.

In the summer of 1965, the electronic sounds employed by The Beatles, Stones, Beach Boys and Byrds were lighting up the airwaves, and, if anyone knew how to ramp up the volume, it was Paul Butterfield.

With the program long set for the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, fate once again stepped in, this time in the form of Peter Yarrow — the Peter in Peter Paul and Mary and member of the festival’s board.

Calling a last-minute meeting of the group, Yarrow urged members to include the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the opening day line-up. Stalwarts of the old school sounds balked at the idea, but Yarrow, who seemingly had a lot to lose by changing the course of folk music, urged them to look at the bigger picture, realizing that if they kept on as they were, ignoring the way the genre was trending, there might not be a Newport Folk Festival in ’66.

In the end, the board sided with Yarrow, and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, with Michael Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop on guitar, Sam Lay on drums and Jerome Arnold on bass, took to the stage.

Despite a demeaning introduction by music critic/folklorist Alan Lomax, (inciting a bit of a brawl between Grossman and the critic) the band played on, and the crowd roared.

Maria Muldaur was in the audience that day and recalls the palpable electricity. “They just blew our folkie minds… Everyone reacted to the power and energy,” she says, “and the audiences loved it.”

Paul Butterfield had been at the right place at the right time with the right sound, riding the wave of change and making it his own. Years later, time would not be as kind. But one thing was clear: The Paul Butterfield Blues Band — as he noted, “made the electric blues a viable form of popular music.”

Riding on the coat-tails of their Newport success, the band spent most of 1966 on the road, playing colleges, clubs and concert halls, including, notes the film, a substantial amount of bookings in San Francisco, thanks to concert promoter Bill Graham.

Seizing the opportunity to pay back his Chicago blues heroes who had eased his way into the clubs, Butterfield would encourage Graham to book them in these larger venues, enhancing their bank accounts, bankability and fan base.

When the band wasn’t on the road, it was in the studio recording a second album, the eclectically diverse East-West.

The 1966 release covered a lot of musical territory, with cuts ranging from electric blues to psychedelic rock and what has been described as “some of the earliest jazz-fusion and blues-rock excursions.”

By 1967, there was a noticeable change in the make-up of the band as well, with old members leaving and new members like Bugsy Maugh on bass guitar, and a brass section consisting of Gene Dinwiddie on tenor sax and Keith Johnson on trumpet signing on.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, June 1967 on stage at the Monterey International Pop Festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California

This new configuration was on display at the Monterey International Pop Festival that year, as well as on the band’s next album, Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw, which saw Phillip Wilson (drums) and David Sanborn (alto saxophone) joining the group. It would be Sanborn’s first professional gig. “Being on stage with him was like a hurricane,” says Sanborn. “The sound was ferocious.”

Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw saw the band moving farther away from its Chicago blues roots, and closer to the more commercial brassy sounds of the day.

The following year My Own Dream was released, taking yet another step back from the sound Butterfield had built his career on.

By 1969, Paul (now the only member of the original band) and his new group headed for Woodstock, where they blew the virtual roof off of the festival.

Butterfield rounded out the decade with a tribute album called Fathers and Sons, an homage to the old guard, as in “You’re the fathers, and we’re the sons.”

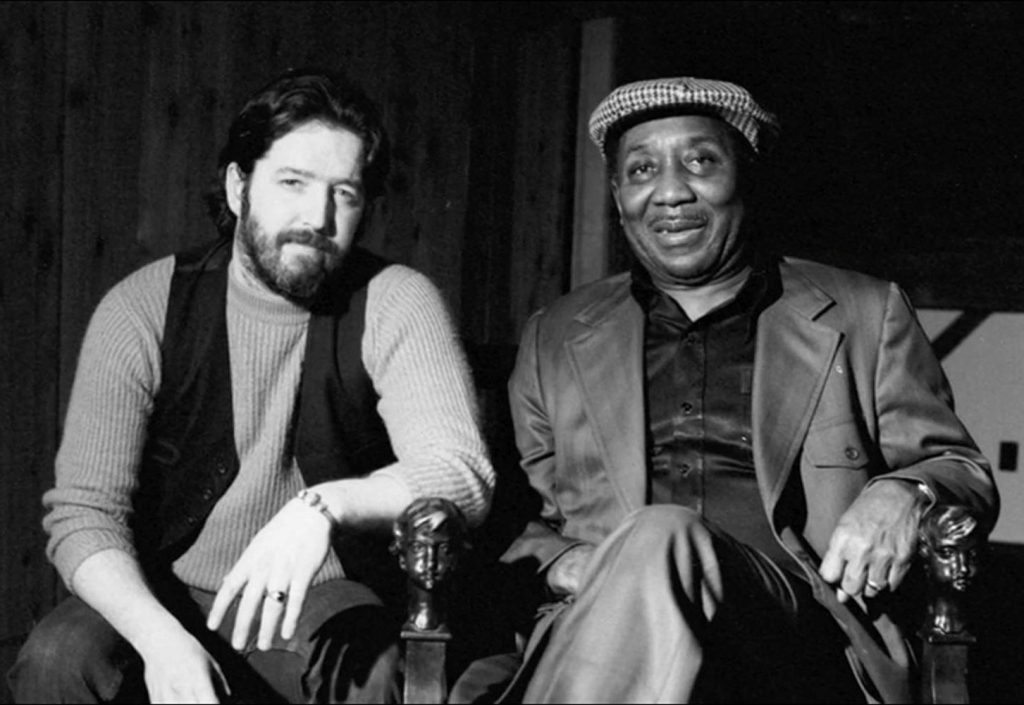

Paul and Muddy Waters Walkin’ Through the Park

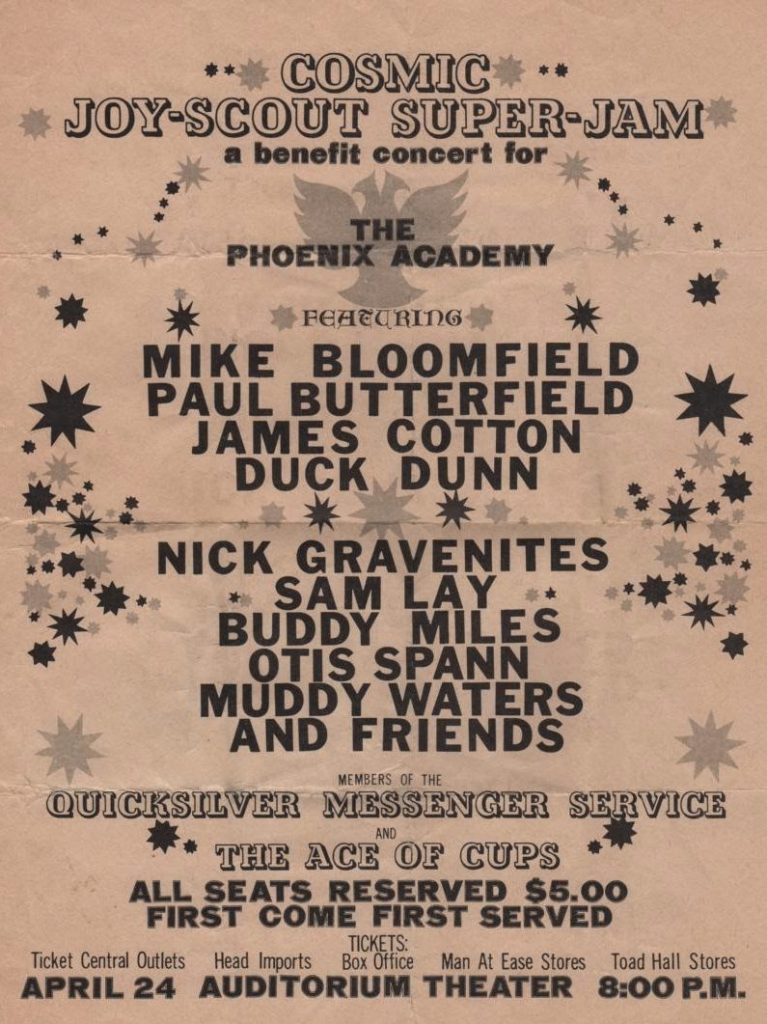

Co-produced with Marshall Chess (son of Chess records’ founder Leonard Chess), it was unique in that half of the tracks were recorded in the studio, the other half in concert. And what a concert it was, with Butterfield, Bloomfield, James Cotton, and Duck Dunn headlining, and a long list of great bluesmen including his old friend and mentor, Muddy Waters.

In the summer of 1969, the band was invited to Woodstock, where they were well-received. Their album, Keep on Movin’, less so.

As the decade drew to a close, so did Virginia and Paul’s marriage, but they had had a son together and a deep respect for each other, and would remain friends, to the point where it was Virginia who would deliver the eulogy at Paul’s funeral some 17 years later.

Butterfield would marry again, this time for no other reason than that he was loved and in love. His wife, Kathy, would play an important role in his life, cheering him on, allowing him to be what he wanted to be and do what he wanted to do, while giving him a stable family life and doing her best to keep him from being his own worst enemy.

They moved to Woodstock, New York, where Albert Grossman had a state-of-the-art recording studio, in 1971. Famous for the music festival that bore its name, Woodstock was much more than that: an artist’s colony, where artists and musicians lived and worked, supporting and championing each other’s dreams and ambitions, inviting neighbors over for cookouts, jams and good times. And it was a good time for Paul and Kathy Butterfield and their blond-haired baby boy, Lee.

Happy Traum, musician and founder of Homespun Tapes, remembers the day Paul and John Sebastian — two of the harmonica’s greatest players — came into Grossman’s studio and put down a track Traum describes as “the most beyond-belief version of Amazing Grace.”

“It was so perfect, and we were all sitting there and just completely open-mouthed and silenced by this incredible thing, and then it was over,” he says. “Paul got in his Jeep and went back down the mountain”.

Paul Butterfield and John Sebastian from the 1977 LP “More Music from Mud Acres”

Happy would later record Paul talking about the harmonica, the players he admired and the way they and he approached their music. The recordings are part of a series of instructional audio tapes that are now available on CD. Horn from the Heart includes a small piece of that conversation.

Once ensconced in the Woodstock community, Paul continued to perform, generally flying to one gig or another on weekends, while leaving more than enough downtime to enjoy being a husband and dad, and even interacting with neighbors.

Walking By Myself: Paul Butterfield, Michael Bloomfield, Mark Maftalin, John Kahn and Billy Mundi reunite at the Fenway Theater in Boston, Massachusetts at a reunion concert in 1971.

There was also time to record a seventh album, 1971’s Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin’, which proved to be somewhat of an ironic title given the fact that the roof was about to cave in.

With disappointing record sales (and focus on more commercially successful artists), Elektra dropped the band, and the gigs became fewer as music took yet another turn. Sadly, this time around Paul would be on the other side of the curve, with the sounds of the ’70s lighting people’s fire. It was as if someone threw a switch and the lights went out.

Jim Rooney, then manager of Bearsville Studios, recalls the way it all went down. Rather than getting a call from Elektra or Albert Grossman, Butterfield found out that the band had been dropped when plane tickets to a weekend gig failed to appear. Calling the agent who booked the band’s travel, he learned that Albert Grossman hadn’t been paying the bills for a good while and any travel plans were on hold.

“By this point, Janis Joplin had died and it seems to me that the wind went out of Albert’s sails,” says Rooney, “and the next thing I know, the Butterfield band is dissolved. And it happened really fast… And that’s a huge blow… I don’t think Paul ever recovered from that.”

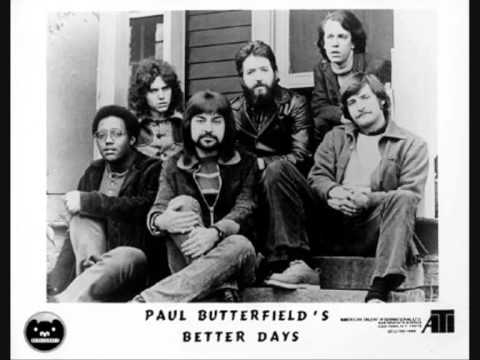

Grossman would do his best to compensate Paul for the loss, offering him a recording contract with his own label — Bearsville Records. The resulting album, Better Days, saw Paul backed by a talented group of musicians, including Geoff Muldaur, Ronnie Barron, Amos Garrett, Christopher Parker and Billy Rich.

A live performance from one of the album’s best known cuts, He’s Got All the Whiskey (LIVE) 1973, at the Record Plant, Sausalito, CA, December 30th, 1973. With Paul, Ronnie Barron (piano, vocal), Amos Garrett (guitar), Rod Hicks (bass) and Christopher Parker (drums).

They would record three albums — Paul Butterfield’s Better Days, It All Comes Back, and Live at Winterland Ballroom. Recorded in 1973, Winterland Ballroom would be shelved until 1999.

After two years, mostly on the road, the band disbanded and it looked as if the harp player’s “better days” were behind him. He would spend the next two years working solo or as a sideman or session player, appearing on — among other artists — a Bonnie Raitt album, and Muddy Waters’ Woodstock.

Despite such high notes, Paul’s career was at a standstill and fading fast. Put it in Your Ear — his attempt to latch on to the disco craze — received lackluster reviews, and his escalating alcohol and drug use, coupled with long stints on the road, had taken its toll on both Paul and his family. In 1976, Kathy Butterfield had had enough. The marriage was over, and she and son Lee packed up their cares and woes and moved west. Paul’s attempts to reconcile were thwarted by his inability to kick his habit. The marriage was over.

Sometimes love is not enough.

And then, a lifeline in the form of an invitation to participate in The Last Waltz.

Billed as The Band’s ‘final’ concert, it was a star-studded event, with Butterfield sharing the stage with the likes of Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Muddy Waters.

Filmed by Martin Scorsese, the resulting documentary would be released some two years later.

Paul Butterfield Blues Band “Walking Blues” 1978

In 1980, Paul collapsed while working with legendary Memphis producer Willie Mitchell on his North-South album. The diagnosis: Peritonitis, which the Oxford dictionaries describe as “an inflammation of the peritoneum, typically caused by bacterial infection either via the blood or after rupture of an abdominal organ.”

Exacerbated by his escalating use of alcohol and hard drugs, which now included heroin, the painful condition would lead to multiple surgeries and hospital stays.

Despite everything, Paul Butterfield managed to complete the North-South album, hoping that it would duplicate the success of the similarly-titled East-West some 14 years before, but critics were less than thrilled.

It was the end of an era, with Paul selling the Woodstock house and moving back to New York City. Nearly out money and options, in pain, and with a habit that needed tending, his career appeared to be all but over.

And then, and then — another lifeline, when an investor-banker bankrolled a comeback album.

The Legendary Paul Butterfield Rides Again, was released in 1986.

Butterfield performs Why Do People Act Like That from The Legendary Paul Butterfield Rides Again

But it was too little, too late.

Moving to LA to be near Kathy and Lee, beaten up and in pain, Paul would be in and out of rehab, managing to pull it all together for a B.B. King TV Special in April of 1987. But the ride was over.

Paul Butterfield, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Albert King From 1987’s B.B. King and Friends.

A month later, after performing at a Pittsburgh club the night before with Rick Danko, Paul Butterfield was found unconscious in his hotel room and rushed to the hospital. Disregarding doctor’s orders, he checked himself out as soon as he was able, and flew back to LA, where he would die a week later from what was officially determined to be an accidental drug overdose.

He was 44 years old.

It was a sad ending that would, for a time, overshadow the legacy he had carved, paths he had forged and difference he had made.

Nearly two decades would go by before the bluesman would be posthumously inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, and another nine before The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Paul’s son Gabriel accepted the honor on his dad’s behalf.

And that would have been that, had Sandra Warren not picked up the gauntlet.

After a long and rewarding career as an attorney, Warren retired in 2010, giving her more time to pursue her music passions. One day, while listening to Sirius radio, she heard the song that first made her aware of Paul Butterfield and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. “It reminded me of how important he was to me,” she says, “and rumbled around in my mind.”

Recalling how Butterfield had changed the way she thought about music, and the contributions he had made to the blues, she started poking around the Internet and was surprised to see that there was just a smattering of archival footage and audio recordings other than his albums, and not a single book or film devoted solely to his life.

“I did a Google search to see what people were saying about him,” she recalls, “and I came across a band playing in New York called the Butterfield Revisited band.”

Taking her Paul Butterfield LPs with her, she went to hear the band and was happily surprised to find that Paul’s son Gabriel was the band’s drummer.

“I met him and we talked, and I met other family members,” she says, “and the idea of having a documentary out there that would cement his legacy became a mission for me. And one thing led to another.”

Enter John Anderson, a seasoned filmmaker with an Emmy and number of nominations to his credit, and a resume that included work for nearly every major network and studio from PBS to Disney.

Anderson knew the territory, having directed two blues-centered documentaries: 2008’s Born in Chicago and 2014’s Sam Lay in Blues Land.

His experience and talent were underscored by his understanding of the blues genre, familiarity with the players, and a deep respect for Butterfield’s music.

“I saw him at the Pops Festival in 1969,” he says, “and his intensity stayed with me.”

Shortly after that first meeting, the two hit the ground running, with Warren taking on the role of executive producer, and Anderson wearing a variety of hats: writing, directing, editing, narrating and co-producing the film.

As for the film’s title — Warren says it comes from something Butterfield said as part of that series on Homespun Tapes.

“One of things that helped me in learning to play the harmonica was that I realized that I could never speak the way any other individual spoke on the harmonica. Each has their own way of saying things. So I just went ahead and got to a point of learning the instrument well enough that I could speak the way I wanted to speak, which is really a nice thing about this instrument: it’s such a personal instrument. It’s really like a horn from the heart.”

There was no need to look any further; Horn from the Heart it would be.

Backed by a dedicated team, Anderson and Warren set to work uncovering long-lost footage, photographs and other materials, and interviewing those who could fill in the blanks.

Among those sharing screen time, the late B.B. King, Paul Shaffer, Maria and Geoffrey Muldaur, Bonnie Raitt, Todd Rundgren, Jim Kweskin, Michael Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop, and other band and family members, co-workers and neighbors, each with his or her own take on the man and his music.

The resulting film, unlike some brushed-over, high-gloss, bio-pics, tells it like it was, giving the viewer a full picture of this complicated but gifted artist.

The clips and quotes and makeshift travelogue of Butterfield’s life in this article are but a sampling of what you’ll find in the film. It is a remarkable portrait of a man who, in no small part, changed the way people thought about the blues and challenged the ‘great divides’, be they black versus white, Chicago versus Delta, or acoustic versus amplification.

At his best, Paul Butterfield loved long and hard, won the respect and admiration of those he worked with and turned the genre upside down, which, as it turns out, was the way he held his harmonica.

For those who hold the instrument close to their heart, Horn with a Heart is a must-see.

For more information on Horn from the Heart: The Paul Butterfield Story, go to www.hornfromtheheart.com.

Comments

Got something to say? Post a comment below.