Jerry Portnoy discovered the harmonica at a friend’s house sitting on a mantle. He’d faltered trying to learn instruments that required his hands but something about the instrument spoke to him. Portnoy quickly became obsessed and, in the forthcoming decades, backed up some of the greatest blues musicians to ever live like Muddy Waters and Eric Clapton. Portnoy is now regarded as one of our living harmonica masters and one of the few remaining harmonica players with a direct conduit to the formative musicians who built Chicago blues.

Do you remember when you fell in love with the instrument?

It was in 1968. I was living in San Francisco at the time and preparing to go to Europe. I was at a friend’s house and he had a harmonica on the mantelpiece. I had tried other instruments and they all required some form of digital dexterity. A harmonica was strictly an oral instrument, breathe in and breathe out. I thought I could do it. My friend told me to take it when I went to Europe. I was hitchhiking around Europe and when I was in Sweden I saw a Sonny Boy II record. He did a few albums when he was in Europe (with the Animals and The Yardbirds) and this was one of them. The front cover showed a profile photo of him with the harmonica in his mouth lengthwise like he was going to swallow it. I went back to the place I was staying and put it on the record player and that was it. I thought it was the coolest shit I ever heard and I had to do it.

So how did you learn to do it? Were you like a lot of people in that time period – putting the record on and then pulling the needle off at a certain location?

There were a lot of portable record players back then. You’d pull down the turntable so it laid flat and pull out the speakers on either side. I would sit on the floor with my head between the speakers and my arm within reach of the needle. I would play something over and over until I could fix it in my head and learn how to play it. Record players had four speeds and 16 RPM was just about half of 33 RPM. If you’d play a 33 ⅓ speed it would stay in pitch but slow it to almost half speed and drop it an octave. The sound was different.

I spent hours just listening to records and that’s how I learned. I trained my ear. I don’t believe in tabs and think it can hinder your learning. If your ear doesn’t function properly you won’t learn to play.

The players you studied were largely big tongue blockers. Did you learn that technique from listening or did you pick it up elsewhere?

I learned that replicating the right notes at the right time structure on the harmonica was not replicating the music. There are so many nuances of sound like the vibrato and percussive effect. You have to pay attention to those details. I pursed for about six months before I figured out blocking. For about ten years I tongue blocked everything. After a while I realized I needed my tongue for other things like triple tonguing and it couldn’t always lay on the harp. So I went back to learning how to play pursed. Now I use a combination depending on what kind of sound I want to make.

When you were learning, Paul Butterfield was big and the harmonica was branching into an aggressive, rock based approach. Did any of that speak to you or was it always the classic players?

A lot of that stuff was taking blues and making it more accessible to the public. The Allman Brothers did a song by Freddie King that was actually done by Tampa Red. The process of learning the blues is a process of going backwards. A lot of those guitar players want to be Stevie Ray Vaughan. But what Stevie did was learn things from the ground up and incorporate all of it. His own self emerged as a product of absorbing all of these influences. People that want to play like Stevie are just skimming the surface.

As you played with Muddy, what did you learn about phrasing and putting together musical ideas?

When you look at all the great blues players with the exception of the genius Little Walter most people had a bag of tricks and licks. A lot of it was alterations and recombinations of the same material. Muddy’s slide solo came from a template that got altered every night. John Lee Williamson, the foundation of blues harmonica playing, had a certain approach that involved eight or ten basic moves and everything was a recombination of those. As far as improvising goes it takes a certain amount of bravery – what Eric (Clapton) called an act of faith. Once you know your instrument well enough and have done a certain amount of homework you can start to let go.

All great art comes from the unconscious. You have to let go and let the music take over. At the highest levels of improvisation you are just a conduit. You translate instantly because you are competent enough to transfer what is coming through you.

At the start you are just taking licks and trying to jam them in and see if they fit. You always hope for the magic and the moments when the instrument plays itself. (Little) Walter said he just filled the harp with air and navigated and that’s a good metaphor. When you get that groove you are breathing in time with music. The harp will then move on its own because you know how notes will relate to each other.

Let’s say you had to solo after Muddy or Clapton and you tried to tap into that bigger universe. How would you approach that? Pick up on something they played?

It depends on the moment. You might pick up on a lick they did and use that as a jumping off point. You might play the same thing every time. But when you are really playing free you pick up on what’s moving you. If I could bottle it, shit, I’d be a millionaire.

We’re at a time when virtuosity on the instrument is at an all time high, possibly because of access to information on the Internet and YouTube. People have the ability to play very sophisticated music on the diatonic. Is something getting lost or are these developments good overall?

Serving the music can get lost. If people want to just show off their skills and virtuosity that’s an empty display. It has to serve the music and the song. Whatever serves it best is what you use even if it’s one note. You can’t lose sight of the purpose of the music which is to communicate a feeling. If the feeling you want to communicate is “look Ma, no hands!” that will impress people who are easily impressed by the wrong things but to good musicians it’s meaningless. If it takes one beautiful note in the right place that’s what you need. What moves people in music is often not your note selection – what moves them is the literal sound of the note. The first order of business to make a beautiful sound. Then, know where to put it.

What are some of the biggest lessons you’ve learned about phrasing over your lifetime of studying Little Walter? What does his example continue to offer us?

Inspiration. The beauty of his playing is timeless. I am always amused because when he was doing this it was bar music in black clubs in Chicago. After World War II, amplifiers were introduced and that aligned with the great migration of black people from the south to the north. That was the origin of Chicago blues.

I wanted to ask you about Blues For Big Nate. I learned it years ago although I could do it more justice now. I always thought the song was a masterpiece of tasteful phrasing.

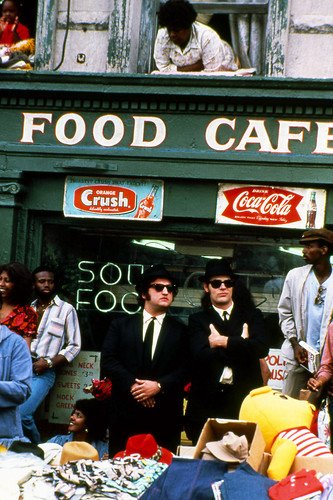

That song was a one off! I’ve always loved playing slow blues. You know the scene in The Blues Brothers at the soul food cafe where John Lee Hooker and others are playing on the street? That was a real place. When I was a kid that little cafe was a deli. In about 1981 I went back there but it had been sold to a guy named Nate Duncan, who was “Big Nate.” I said to the woman at the counter, “Didn’t this used to be called Lyons?” She pointed to this big guy behind the counter and said, “This is Nate and he’s been working here since he was a kid.” I talked to him and said my father Max Portnoy had a store down the street. His jaw dropped open and he said, “You’re Jerry Portnoy! You’re The Champ’s son.” My dad was known around Chicago as The Champ. He then told me that my father was the greatest and he taught him all this stuff. From that point forward I never went to Chicago without visiting Big Nate.

What do you still love about the instrument at this point of your journey?

When the magic is happening and I hit that spot and zone where the instrument plays itself. The greats like Walter or Kim Wilson can just turn on the spigot. The rest of us turn it on and sometimes there is a stream or a few drops, and sometimes it comes in a rush. When the instrument starts to play itself and I am a conduit it’s almost indescribable. If you open up and trust enough to let the music guide you it can be the best feeling in the world.

Comments

Got something to say? Post a comment below.